- Home

- Jonah Lisa Dyer

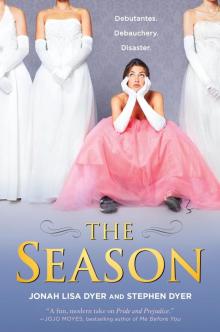

The Season

The Season Read online

Viking

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

First published in the United States of America by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2016

Copyright © 2016 by Temple Hill Publishing

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

eBook ISBN 978-0-698-40334-5

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE.

ISBN: 978-0-451-47634-0

Visit us at www.penguin.com

Version_1

For our dads, who kept the lights on for a long time.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

One

In Which Megan Learns Why It’s Called a Sucker Punch

DOWN A GOAL IN INJURY TIME LACHELLE BEGAN A buildup inside midfield, passing it down to Mariah, who fed Lindsay in the right corner. Lindsay beat her girl to the end line, then fired a low cross toward the goal mouth. Cat streaked in, carried her defender and the goalie’s attention, and then dummied it—let the ball go through her legs untouched. It was beautifully done, a play we had worked on endlessly. I was now just eight yards out; the wide-open net yawned. All I had to do was ease it home. But overeager, with visions of my highlight reel playing in my head, I hammered it. The extra oomph lifted the ball—and it caromed off the crossbar and out of bounds.

The crowd groaned and I stood there—gutted. I had just missed a gimme that would have tied our first conference game. Well done, Megan, I thought. Well done. A minute later the whistle blew. University of Oklahoma 2, Southern Methodist University 1.

I kicked over the watercooler, and was working my way through the sideline chairs when Coach Nash found me.

“Hey, stop that!” she yelled. She frowned, and her disappointment washed over me. “What’s the lesson?”

“Don’t be a freaking moron?” I asked.

“Composure,” she said to me for the nine hundredth time in the past year. “No matter the moment, you have to keep your head, execute under pressure. Consistently good is far better than occasionally brilliant.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“I’m not interested in your apology.” Ouch.

“I let everybody down,” I said, hanging my head.

“Yes. You did.” Ouch again. But now she lifted my head and looked directly in my eyes. “Now listen—you are going to score a ton of goals for us this year.” Her tone softened as she moved easily from Marine Corps drill sergeant to mother hen. “It’s going to all come together, okay?”

“Okay.” I nodded again and she gave me a hug.

“Short memory—and get that looked at.” She motioned at the gash on my shin.

“Uh-huh,” I replied, still feeling like someone had shot my dog.

“I’ll see you on Monday.”

Now Cat shuffled over. Catalina Esmerelda Graciela “Cat” Martinez was my best friend on the team, my wingman, and the only one brave enough to approach me under the circumstances. We had known each other since we were twelve and had played Club Soccer together for the DeSoto Bobcats—now we were Ponies. I went to her quinceañera and famously destroyed her piñata with my first whack. They found candy all the way down the street.

“Come on, choker,” she said, putting her arm around me. I laughed. As always it was just the right thing to say.

“You go. I want to sulk.” Now she laughed.

“All right. You need a hankie or something?”

“Nah—I got my sleeve.”

“We’re on for Tuesday night, yeah?” Tuesday was TV night, sacred friend time.

“Of course,” I said as she walked toward the locker room.

“Text me later!” she called out over her shoulder.

With everyone gone I sat down and examined my shin. Blood oozed along the entire ridge of welted skin. Another scar—and so little to show for it. In soccer, real scoring chances are rare, and my job as a striker was to make good on them. My failure today cost us a very valuable point. I picked some grass out of the cut, squinted over the edge of Westcott Field into the late August sun, and wondered how things could get any worse.

I wasn’t kept waiting long.

“Hey.”

I looked up to see my sister, Julia. She was taller and prettier than me, with blonde hair, startling light blue eyes, and creamy, blemish-free skin. Few would guess that we were twins—the clear result of two eggs, not one.

“You see the game?”

She nodded, but stayed several feet away. “Hate to pile on, but I thought you might want to see this.”

Julia handed me her phone, the browser open to The Dallas Morning News.

Bluebonnet Club Announces 2016 Debutantes, the headline read. I scrolled through the article. Blah blah blah proud to announce Ashley Harriet Abernathy, Lauren Eloise Battle, Ashley Diann Kohlberg, Margaret Abigail Lucas, Julia Scott McKnight, Megan Lucille McKnight, Sydney Jane Pennybacker . . .

Wait, Megan Lucille McKnight?! There must be some mistake, because that was ME!

“Did—did Mom call you?” I asked.

“Nope.”

“Text?”

Julia shook her head. I wanted to splutter in disbelief. To scream, to rage, to protest violently. But my mother was thirty miles away at the ranch. I read on.

At the bottom were the pictures. Seven toothy, varnished girls soon to take their anointed places in the pantheon of Bluebonnet debutantes, that rare and coveted role in a tradition that dated all the way back to 1882, as Mom had so often reminded us. My picture was a real doozy, taken as an olive branch to her after she complained for years that the only photos she had showed me posing on one knee beside a soccer ball.

For this timeless memento she’d spared no expense. She had hired a stylist, bullied me into a low-cut Stella McCartney, and chosen a photographer who insisted on shooting in the gloaming, down amongst the crepe myrtles along Turtle Creek. Resting my hand oh-so-casually on a branch, smiling at a hundred miles an hour, I looked like a hick who’d lucked into a makeover coupon. Never in my worst nightmares had I imagined it would pop up a year later in the city’s most widely read newspaper, beneath an announcement for a virgin auction.

“Maybe it’s a mistake?” I said hopefully, handing back her phone. Julia kept silent. She had passed AP calculus as a sophomore in high school and was majoring in structural engineering. Like a lot of really smart girls, she learned early that silence was often a wise tactic.

“All right,” I said. “I’ll shower and we’ll go see what she has to say for herself.”

Julia smiled, a tad too brightly.

“I’ll make popcorn,” she said.

Julia drove so I could elevate my leg. No stitches required, but the trainers rinsed it liberally with hydrogen peroxide, squirted some Neosporin in, and applied a gauze bandage, telling me to keep it up for a while to stem the bleeding. So on the half-hour drive from Dallas to the ranch, I propped my leg on the dashboard and multitasked by staring out the window and fretting about why my mother would want to ruin my life. Julia, still in the throes of her breakup from her longtime boyfriend Tyler, chose Tame Impala for the gloomy soundtrack. The only thing missing was rain.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that all daughters eventually conclude their mothers are insane, and though I had long heard the rattle of loose nuts and screws in Lucy McKnight’s head, even for her this challenged belief. I simply wasn’t debutante material. Not even close. And I’m not being modest. I wore faded Wranglers, old T-shirts, and Ropers, except when I mixed it up with baggy nylon shorts and flip-flops. I bought Hanes sports bras and cotton panties in saver packs. I had freckles and a farmer’s tan, and my hair, best described as “brown,” was forever in a ponytail, except during practice and games when I added an Alex Morgan headband crafted from pink trainer’s tape. My lips were permanently chapped, as I lived in a state of semi-dehydration, and my nails were ragged and dirty. My muscular legs were a war zone, and my upper body was lean as a stewing chicken from thousands of hours running in the Texas sun.

“She’s finally gone full-on, bat-shit crazy,” I said to Julia, who pursed her lips, maintained her silence, and kept her eyes on the road.

Now Julia as a debutante, that made some sense. She was delicate as a Japanese sliding door, and boys fell for her like leaves in the fall—by the thousands. Frankly she was precisely the kind of girl I might have sneered at and despised—a Pi Phi, well-dressed, well-mannered, a successful student, and so good at all those girlie things I could never master, like batting her eyelashes, applying makeup, and flirting. But as she was my only sister and my womb mate, I loved her intensely, and woe to those who threatened her.

She took Exit 47, the only exit on South I-35 we ever took, and turned left onto FM 89. Another mile and we would be at the ranch. When I saw the edge of the buck’n’rail fence that marked the western boundary of the Aberdeen, I set my leg down gently and prepared for battle.

“MOM!” I thundered. “MOMMMM!”

No answer. I stood in the front hallway of the main house. She’s hiding, I thought, afraid to show herself. Coward.

Julia, purse hooked over her arm, came in behind me. She was clearly entertained, like a kid watching floats at an Independence Day parade. I scowled and went around the staircase, down the hallway, and through Dad’s closed study door like the Germans through Belgium.

When the door hit the wall he bolted upright.

“Hey,” he said, blinking. A college football game played on the TV. Bless his heart, he had been napping on the couch. His dusty boots were under the coffee table.

“Something you’d like to tell me, Dad?” I demanded.

“No,” he said, slowly. Julia, content to drift in my wake, wandered in behind me.

“You know, when you offer your daughter up for sale, the polite thing to do is to tell her.”

Ahh, now he remembered. He ran his hand through his hair, bought a moment. At forty-six, he had hair that was still tawny and full, with just a swatch of gray at the temples. A lifetime of squinting in the sun had seared in creases around his hazel eyes, but he was still boyish and handsome. Fit too—the daily grind of cutting cattle on horseback kept him rangy and tough as a fence post. Angus McKnight III looked like exactly what he was—a working cowboy.

“Honey, you are not being offered up for sale, and I was as surprised as you were about the announcement.”

“I doubt that,” I said, giving no ground. Dad tried his most sympathetic look on Julia, hoping for support.

“Of course we were going to tell you—” Footsteps in the hallway. Dad looked over my shoulder. Could it be the cavalry? Indeed.

My mother, Lucy McKnight, strolled into the study, pulling off her cloth gardening gloves. An inch taller than me at five foot eight, she was still striking, if a little soft around the edges. She was just at that age when women consider the benefits of plastic surgery, and I knew her thinking ran to sooner rather than later, for two reasons. First, you should take your car to the mechanic the minute you hear the engine knock, and second, if done right you might just pass it off on a change in diet and a new personal trainer.

Mom oozed style, and today she managed in that magical, mysterious way only some women can to make jeans, a blue cotton shirt, and a sun hat seem like an ensemble from the Neiman Marcus spring catalog.

“Is that a new purse, Julia?” Mom asked.

“Megan was just asking about—”

“I know why she’s here, Angus,” she said, then turned back to me. “I apologize for you finding out this way. Of course we were planning to tell you this weekend; I had no idea it would run in the paper today. Still, no matter—it’s done and settled.”

“But I told you just last week I didn’t want to debut. Ever. Remember?”

“I took your view into account,” she said mildly, “but I don’t think you understand that this is truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity you simply cannot pass up.”

“Not sure if you’ve noticed, but with school, practice, and games, my plate is full.”

“I considered that, but making a debut is draining both physically and emotionally, and you need to be at your best. I suggest you take the fall off from soccer.”

Good Lord, this was worse than I thought. I tried to stem the molten anger gurgling inside on its way to full volcanic expression.

“Mom, if you think I would take off soccer to waltz and have high tea, you’re more than mistaken—you’re demented.”

“I understand your feelings—”

“No, you don’t,” I snapped.

“I am asking for one season out of what, twenty?”

“You’re asking for one year out of four of college eligibility. And any chance I have at making the national team.”

Her pitying look said it all, but she banged the nail home anyway.

“Sweetie, you’re twenty years old. I think that ship has sailed.”

“I was invited to the regional camp last year!” I had gone to Kansas City for three weeks the previous summer to audition for the Under-20 Women’s National Team, along with about two hundred other girls. Suffice it to say that it was a humbling experience and a quick trip home.

“I know that, current feelings excepted, you will learn so much, grow so much, and make memories you’ll cherish for the rest of your life.”

“Cherish?” I said. “Learning to match my shoes with my purse? To use divine in a sentence?”

“There’s far more to it than fashion and manners,” she said carefully, “though it will be a great advantage to you to work on both.”

“No. It won’t. Because I’m not doing it. You want to send me out dressed like a poodle to parties with cash prizes for ‘Best Idle Chatter’ and ‘Most Vacant Smile.’ Where I’ll be forced to dance with boys I don’t like and be nice to a whole slew of people I don’t know. And you want me to give up a year of soccer for the privilege?”

I paused, took a deep breath.

“Clearly decades of coloring your hair and chugging SlimFast have taken a toll,” I said.

Silence. A step over the line, I realized, as her eyes narrowed and her jaw clenched and her face turned a dark crimson.

“Nobody likes a smart-ass, Megan.”

“I do,” I said cavalierly. “I love smart-asses.” I held

out fierce hope that one day I would meet a boy who liked them too—or else I was screwed.

Mom, a savvy fighter, ignored my jab and closed the space between us. We were now chin to chin.

“Let’s just—” Dad broke in, but Mom stymied him.

“You agreed, Angus.” Dad threw his hands up, and she turned back to me.

“Thanks to a good deal of effort on my part, both you and Julia have been invited to debut this year. It’s practically unheard of for two sisters, and—”

“I don’t care who you bribed.”

“Enough!” she shouted.

I gave her the icy, defiant stare, but she held her ground.

“I love you dearly, but you are headstrong to a fault and quite sure you know all you need to about everyone and everything. Trust me when I say you do not. Three generations of women in my family—your great-grandmother, your grandmother, your aunt, and I—all made our Bluebonnet debuts. Your cousin Abby and your sister, Julia, will make their debuts this year, and while you may not realize what this means, I do. One day very soon your soccer career will end and you will find yourself in a much larger and more complicated world than the one you now inhabit, and it is my job to make sure you are prepared for that. So let me be perfectly clear—this is not a request.”

“This is so unfair, Mom.”

“Is it?” she said. “Is it really?”

The question hung there, and then Mom held the side of her head, obviously in pain. Dad moved in and put his hand on her arm.

“You okay?” he asked. Mom suffered from the occasional migraine, which always seemed to arrive when most useful.

“I’m fine.” But she let him walk her slowly to a chair. She sat down heavily and eyed the sun beaming through the curtains like a vampire would the dawn.

I was furious. Tears welled as my anger burned hotter, but I didn’t know what to say.

“I-I hate you,” I finally mustered. So lame. But committed, I spun and stomped away.

“Honey—” my father started.

“Let her go,” Mom said as I slammed the door for good measure. In the hallway I sobbed and heard her offer the old chestnut “She’ll come around—just let her get used to the idea.”

The Season

The Season